Asepsis Secundum Artem*

(* "According to the Art of Asepsis")

Johnson & Johnson manufactured the first-ever sterile surgical dressings, but what did that really mean? Let’s take a look… Surgery in the 19th century was risky and dangerous, and patients undergoing even the most routine operations literally took their lives in their hands. The primary reason surgery was so dangerous was because it was not sterile. The operating room, the surgeon’s hands, and the surgical instruments were full of germs, which caused extremely high levels of mortality. Surgeons in the mid-1800’s often operated wearing their street clothes, without washing their hands.

19th Century Surgeon's Coat with Needle in Lapel

They frequently used ordinary sewing thread to suture wounds, and stuck the needles in the lapels of their frock coats in between patients. Surgical dressings were also unsterilized, and were often made up of surplus cotton or jute from the floors of cotton mills. It was against this background that

Pasteur’s work influenced the eminent English surgeon Sir Joseph Lister, who applied Pasteur’s germ theory to surgery, thus founding modern antiseptic surgery. To disinfect, Lister used a solution of carbolic acid, which was sprayed around the operating theater by a handheld sprayer.

Surgery Using Lister's Carbolic Acid Sprayer

Although many were slow to adopt Lister’s theory of invisible germs causing surgical infections, it was clear from the greatly increased surgical survival rates that his methods worked. At the time, Lister’s theories were controversial because many 19th century surgeons were unwilling to accept something they could not see – germs – as the culprit. Also, perhaps another reason that surgeons were slow to pick up on Lister’s methods was the fact that carbolic acid had a very strong and unpleasant smell. Sir Joseph Lister was invited to speak at a medical conference during the U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. This event celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and showcased advancements in technology and innovation, among other things. In the audience was Robert Wood Johnson the first, who immediately grasped the importance of Lister’s work and saw an opportunity to create and market the world’s first sterile surgical dressings. This site has a good description of the types of exhibits Robert Wood Johnson would have seen there, and this site has photographs from the Exposition, which show some of the sights that Johnson saw. (Just click on "Tour Centennial Sites" to see the photos.)

Robert Wood Johnson

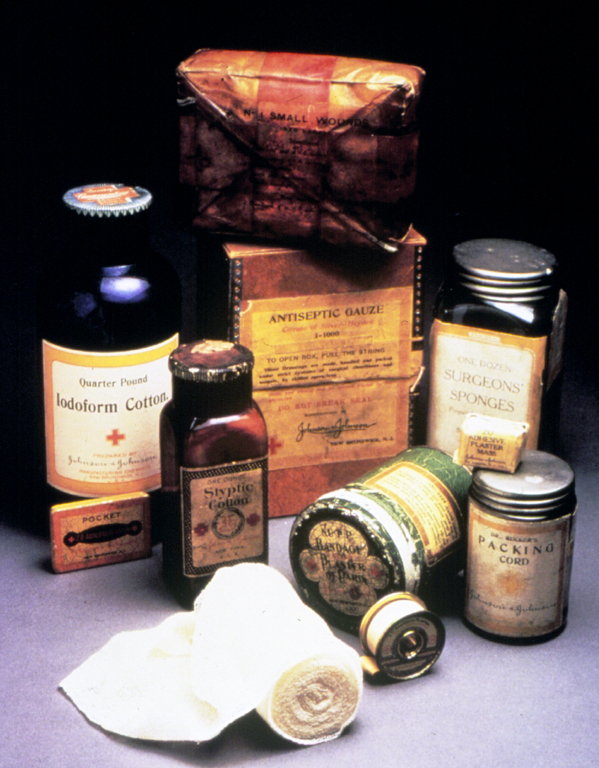

Johnson already was in the medical products business, and his personal experience of having two brothers who fought in the Civil War with its terrible medical conditions also may have spurred him to think about ways to improve surgery. When he and his brothers started Johnson & Johnson in 1886, sterile surgical dressings were among the Company’s first products, as were sterile sutures.

Fred Kilmer published a treatise on sterile wound care in 1897 called “Asepsis Secundum Artem,” Latin for “According to the Art of Asepsis.” Kilmer’s treatise was widely read. A great deal of the scientific data in it was developed in the Johnson & Johnson Bacteriological Laboratory, which had been built to test and enhance improvements in sterilization techniques. The advent of the Company’s sterile surgical dressings and sutures in the market, and its ongoing improvements in sterilization methods, greatly reduced surgical mortality rates.

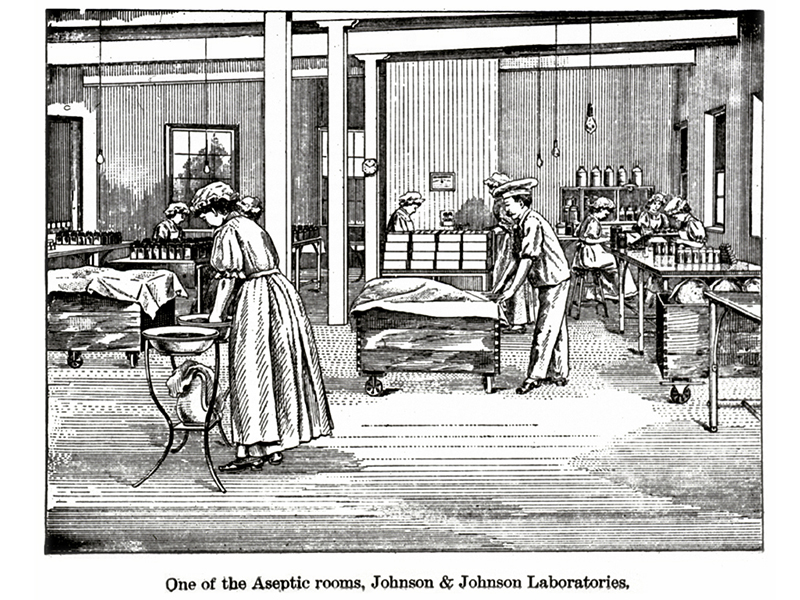

One of the Aseptic Rooms in the Company's Early Laboratories

Wouldn't "Asepsis Secundum Artem,” rather mean “Asepsis according to the Art" ?

My college Latin is fairly rusty by now, so I went and looked this up. Here goes: if you were going to say “the art of asepsis,” “art” would be in the nominative case and “asepsis” would be in the genitive case, so you would say something like “ars asepsorum.” So it certainly doesn’t seem like it’s an exact translation. In writing the blog post, I went with Fred Kilmer’s translation of the title, since he wrote the monograph and that’s how he translated the title and it’s what he intended the title to mean. As a pharmacist and scientist, Kilmer certainly knew some Latin, and in those days he probably studied it in school. For readers who’ve never taken Latin in school, you can put the words in the sentence in any order, usually with the verb last. The ending of each word tells you what part of speech it is in the sentence. So translating Latin is kind of like figuring out a puzzle. If anyone out there is a Latin expert, I would certainly welcome your expertise!

Interesting reading - the history of ASPSIS in opeartion theaters.