1907: The New Cutting-Edge Powerhouse at Johnson & Johnson

Today, the oldest building on the Johnson & Johnson New Brunswick campus – and the only one remaining from the days of our founders – is our museum building. At first glance, the building may look like the steadfast, unchanging reminder of an earlier era. But behind the timeless, rich patina of the brick, that peaked roof and those mullioned windows, it’s an example of the continuing path of cutting-edge innovation at Johnson & Johnson. The museum building originally was the new Powerhouse, built in 1907 to generate electrical power to run the company’s manufacturing machinery.

Johnson & Johnson has been in business since 1886, so it goes without saying that the company employed manufacturing power before 1907. In our first building, power to run the manufacturing machinery was generated by a 200 horsepower engine in the building’s basement.

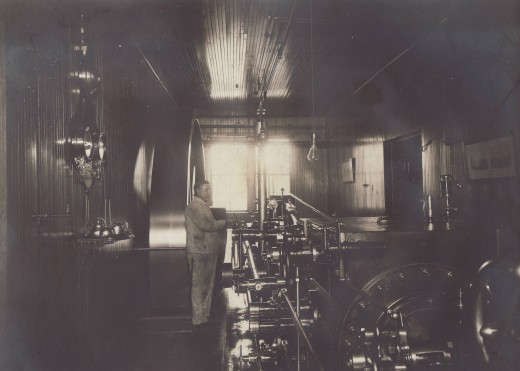

Our next generation engine room was in the Old Mill building, seen here in 1894, with the company’s chief engineer John Hannan at work. (The Old Mill was on the lower part of the campus, directly on the Delaware & Raritan Canal and Raritan River.) Alert blog readers will notice the oil cans on the shelf at the left of the photograph, and the large flywheel behind Mr. Hannan. The flywheel was part of what looks to be a Corliss engine, a steam-powered engine to generate power to run manufacturing equipment, and one of the driving forces of the Industrial Revolution.

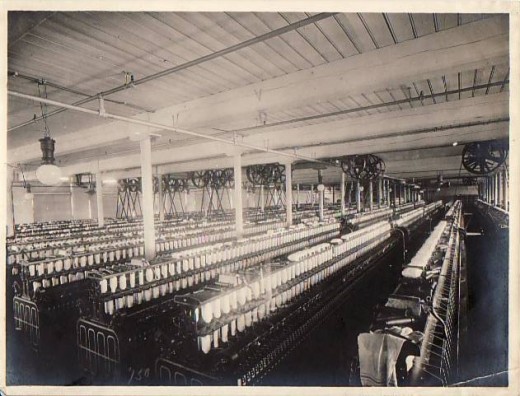

During the late 1800s and up to the mid-20th century, centrally-generated power was transmitted throughout manufacturing facilities using line shafts that ran along the ceiling, with a system of belts and pulleys to power each machine. Beginning with steam power, these systems were converted to electricity before the development of individual motors to run machinery.

In the January, 1913 edition of the RED CROSS® Messenger, Fred Kilmer discussed the constant innovation and re-invention of processes, products and manufacturing techniques at Johnson & Johnson – which was necessary in order for the company to continue to push the boundaries of product innovation and position itself for the future. Even mechanical power was not exempt. “One radical change consisted of the demolishing of all steam-driven machinery, including shafting belts and the like, and the substitution of electric machines in every part of the establishment.” [The RED CROSS® Messenger, Anniversary Number, Johnson & Johnson, Vol. V, No. 8, January, 1913, p. 212]

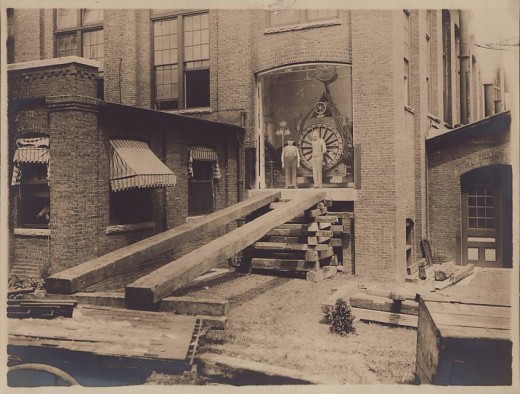

That radical change involved building a new Powerhouse next to the Cotton Mill, which would generate enough electrical power to ensure capacity into the future. Construction was begun under the supervision of the company’s architect, John M----, who designed and built our early buildings. In 1908, Fred Kilmer gave an update on the almost-completed building:

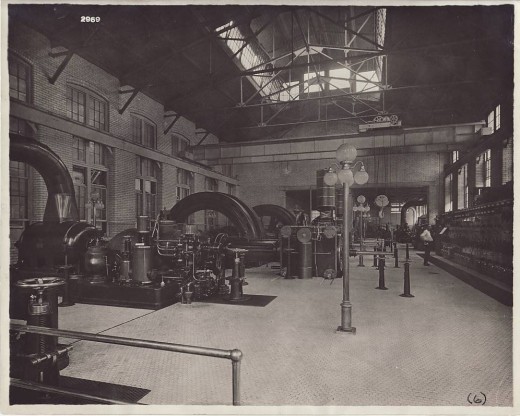

“This electric power plant is nearing completion and is the very latest thing in electrical construction. Sixteen hundred horse power capacity, would arc light quite a large city.” [The RED CROSS® Messenger, Johnson & Johnson, Vol 1, No. 1, May, 1908, p. 21]

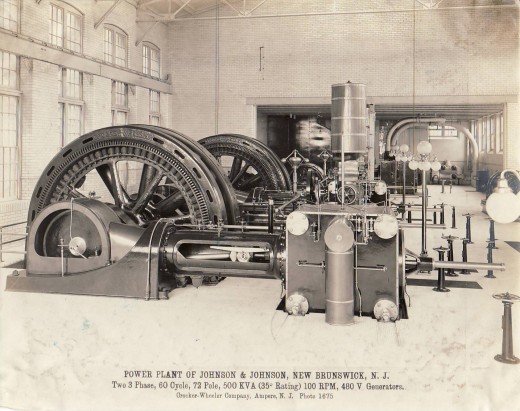

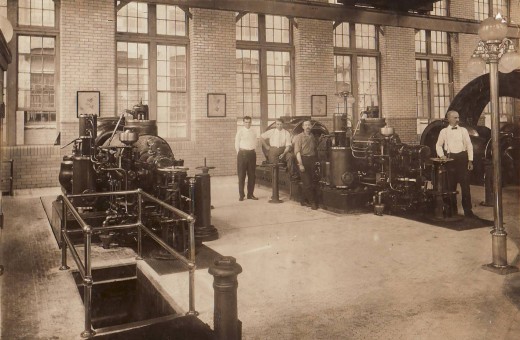

The new Johnson & Johnson Powerhouse used an array of high-powered, large Crocker Wheeler generators. Crocker Wheeler was a major manufacturer of electrical equipment, located in the “Ampere” section of East Orange, New Jersey. (They were so large a manufacturer that they, er, generated an electricity-derived name for an entire section of East Orange.)

That same year, Fred Kilmer reported: “An engine of 1,600 horse-power is used to supply electric power for the entire plant. Under this system belts and pulleys are discarded and very cleanly methods substituted on all apparatus.” [The RED CROSS® Messenger, Johnson & Johnson, Special 1908 edition, p. 8] At 1,600 horsepower, the new high-tech power plant operated at eight times the capacity of the company’s original power plant.

The new Johnson & Johnson Powerhouse was constructed with the same exacting standards as the sterile manufacturing buildings. Its large, mullioned windows and ceiling clerestory let in plenty of light. And the company’s emphasis on a surgical level of cleanliness did not stop at the Powerhouse door: the interior walls were covered in glazed subway tile so that the Powerhouse could be kept scrupulously clean.

Here's a special behind-the-scenes glimpse of the glazed subway tiles, seen today. Uncovered as part of the Museum restoration, the cream and light gray-green tiles with dark grouting still look gorgeous more than a century after they were installed.

In the 1910s, a teenaged Robert Wood Johnson began his career as a mill hand in the Powerhouse. It was there, working side by side with the mill workers, that he would begin to formulate his ideas about the responsibilities of business that would later be expressed in Our Credo, and in his writings such as Human Relations in Modern Business.

As the decades passed and Johnson & Johnson grew and decentralized, the company’s manufacturing moved to larger spaces. The Powerhouse was reinvented first as meeting space and then -- when the company museum moved from its original location in the old Laurel Club building – as the Kilmer Museum, named in honor of Fred Kilmer. General Robert Wood Johnson spent many an hour there, connecting with and drawing inspiration from the long (and continuing!) history of the company’s innovation and caring.

Now, more than a century after it was built, the Powerhouse is ready to reinvent itself yet again, and reclaim its heritage of innovation as we restore the building, uncover its original architectural features and transform the Johnson & Johnson Museum into a state-of-the-art, modern interactive museum in the last of the innovative early Johnson & Johnson manufacturing buildings.

Stay tuned for updates as the project progresses!