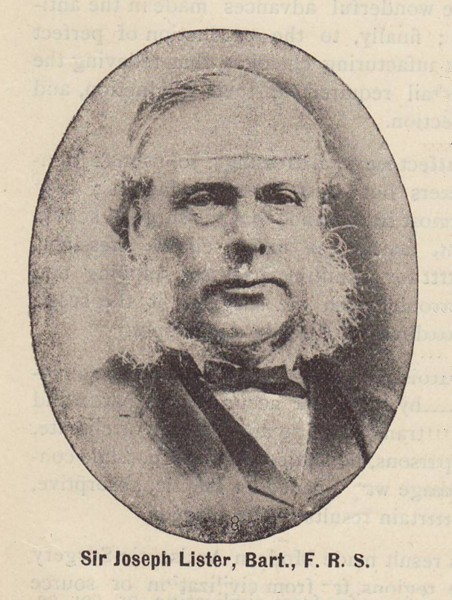

Sir Joseph Lister and Johnson & Johnson: Spreading the Word About Sterile Surgery

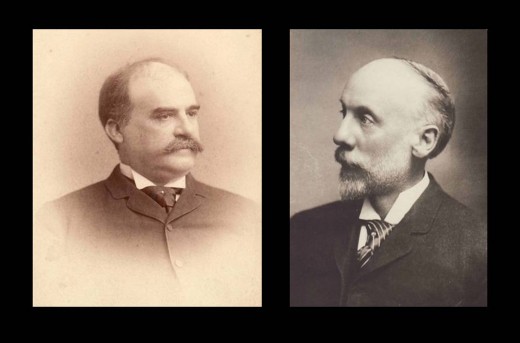

A recent column commemorating Sir Joseph Lister’s April 5th birthday opened with this startling statement: “Joseph Lister, who was born this week (April 5) in 1827, was an amazing physician but a poor salesman.” [“Lister's Life Saving Discovery, by Bruce Kauffmann, Telegraph Herald, Dubuque, IA and the Appeal-Democrat in Marysville, CA] It may have taken some time to inspire skeptical surgeons in the late 1800s, but Lister did inspire two people who were very good at spreading the word, and they took up the cause of making surgery sterile: Robert Wood Johnson and Fred Kilmer.

The writer of this terrific column draws his conclusion about Lister’s seeming inability to get people excited about sterile surgery based on the fact that it took a considerable amount of time for sterile surgery to be accepted by 19th century doctors and surgeons. He cites Lister’s speech at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition’s Medical Congress: Lister’s skeptical audience of doctors was not impressed, even though sterile surgery was clearly the way of the future. But one person in Lister’s audience that day was impressed -- medicated plaster maker Robert Wood Johnson. Lister so inspired Johnson that he and his brothers started Johnson & Johnson and made the first mass produced sterile surgical dressings and sterile sutures to help drive the adoption of sterile surgery.

As regular readers of this blog know, Johnson attended the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition to represent the company in which he was a partner at the time: Seabury & Johnson. Intellectually curious and interested in improving health care, Johnson signed up to attend Lister’s lecture at the Medical Congress. As Bruce Kauffman points out in his column, the American doctors in the audience met Lister’s conclusions with skepticism. In fact, Lister had been invited to speak by some very prominent American surgeons who were determined to discredit his arguments for sterile surgery. With two Union Army veterans among his older brothers, Robert Wood Johnson was probably very familiar with stories about the horrendous conditions of Civil War battlefnield medicine and surgery, and he was a ready audience for Lister. In the audience that day, Johnson understood immediately that surgery needed to be sterile, and he was determined to do something about it.

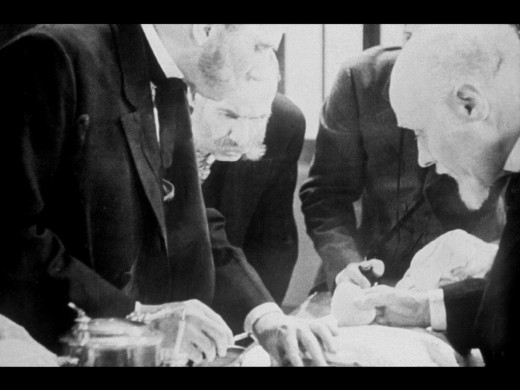

Skepticism aside, if a surgeon in the late 1800s did want to try sterile surgery, he had to make his own sterile dressings and sterilize everything himself – a task that was virtually impossible to do if you weren’t at one of the largest hospitals with a lot of resources. Surgeons used dressings that were made from scraps from the floors of cotton mills, and (readers may want to sit down before they read this description) when they needed to close a wound or incision, they frequently pulled their trusty sewing needle and sewing thread out of the lapel of their seldom-cleaned frock coat, re-using that same germ-filled needle and thread on patient after patient. Surgical survival rates before sterile surgery were heartbreakingly low.

To put sterile surgery within the reach of every surgeon, Johnson wanted to mass produce sterile surgical dressings and sterile sutures. But his business partner didn’t share the same enthusiasm for mass produced sterile surgical products, and that led in part to Robert Wood Johnson and his younger brothers James and Edward leaving Seabury & Johnson in late 1885.

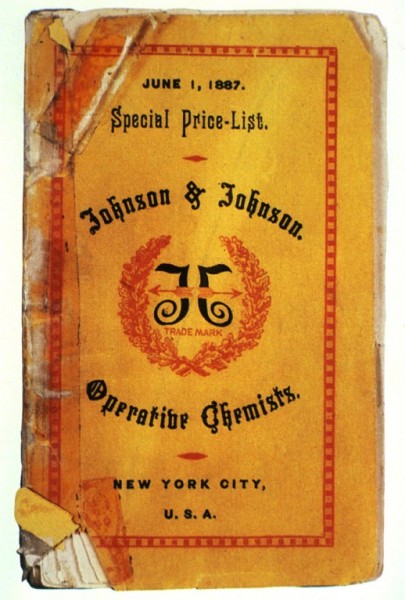

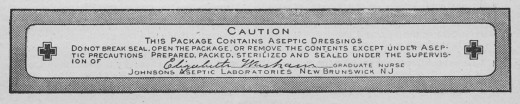

James Wood Johnson and Edward Mead Johnson started Johnson & Johnson in 1886, and when Robert Wood Johnson joined the Company a few months later, we began making those first mass produced, ready to use sterile surgical dressings and sterile sutures, as well as sterilizing solutions for surgical instruments.

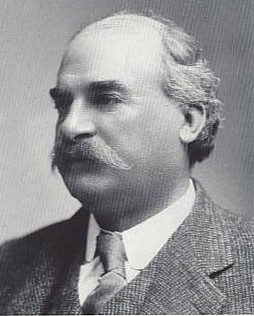

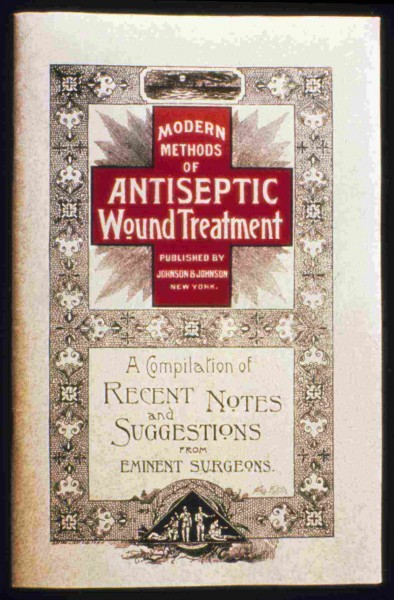

In order to build capacity for sterile surgery and push against the skepticism of the day, Robert Wood Johnson enlisted his friend Fred Kilmer to research and compile a how-to-do-sterile-surgery manual with articles written by the leading practitioners. Johnson & Johnson published it in 1888 as “Modern Methods of Antiseptic Wound Treatment” and gave it away for free to the medical profession. Not only was Fred Kilmer (who joined Johnson & Johnson as our scientific director in 1889) a talented writer, he was a tireless advocate for sterile surgery, and he helped provide the publicity, attention and instructions – combined with his friend Robert Wood Johnson’s mass produced, ready-to-use sterile surgical products – that enabled any surgeon, anywhere, to try sterile surgery.

Johnson & Johnson’s efforts came to the notice of Sir Joseph Lister and, in 1891 he wrote to us asking for details about our methods of manufacturing sterile dressings and sutures. Thrilled to receive a letter from the father of modern antiseptic surgery, Fred Kilmer sent a lengthy reply to Lister, which Johnson & Johnson published in pamphlet form.

So although Lister, as a surgeon, may not have been able immediately to convince his skeptical peers in the medical community that surgery should be sterile, he did inspire two people in the United States – Robert Wood Johnson and Fred Kilmer – who worked tirelessly to make sure that Lister’s dream of sterile surgery became a reality.