Pasteur to Lister to Johnson

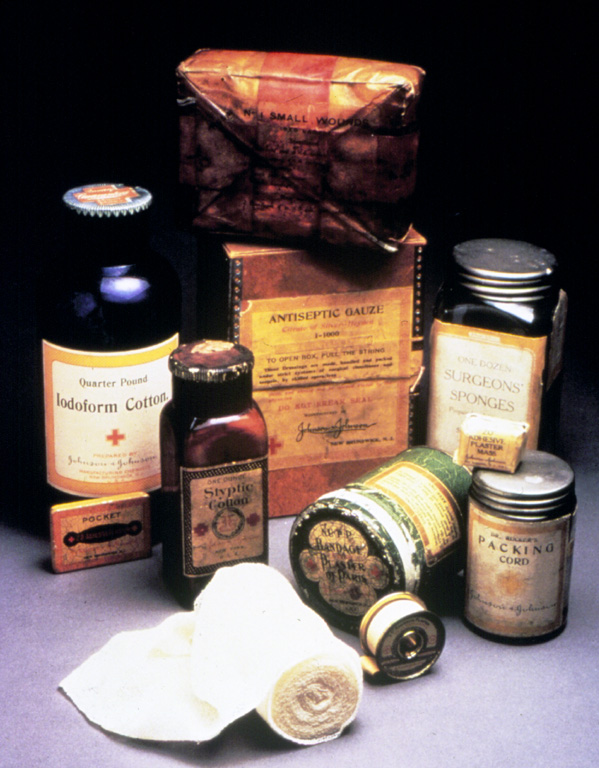

When Johnson & Johnson founders Robert Wood Johnson, James Wood Johnson and Edward Mead Johnson were born in the mid-1800s, one of the most basic developments in science and medicine that we take for granted today -- an understanding of the causes of infection – hadn’t been discovered. During the Johnson brothers’ early years, that scientific discovery and its practical application to surgery would completely transform medicine. In 1886 (125 years ago!), those brothers, now grown up, built on that discovery and its application. How? They started a business to make the first mass produced sterile surgical products, putting them on the cutting edge of a revolution in science and medicine that began while they were growing up.

Throughout most of history, people struggled to explain biological phenomena like the causes of infection, or why some organic compounds like wine, beer, and fruit fermented. The prevailing theory that many people believed – which had its origins all the way back in Ancient Greece and wasn’t seriously challenged until the 1800s -- was that some living organisms spontaneously generated themselves from non-living matter.

Mice: not spontaneously generated. Public domain photo courtesy of, but not spontaneously generated by,Wikimedia Commons.

According to this site, there was even a “recipe” in the 1600s for spontaneously generating mice that involved -- believe it or not -- putting sweaty undergarments and wheat in an open jar and waiting for 21 days, upon which time you would have…mice. (Not to mention a jar that you wanted to throw away.) The debate over spontaneous generation went on until 1859 when Louis Pasteur’s definitive experiment for the French Academy of Sciences demonstrated that invisible microorganisms caused fermentation.

It was a short leap for Pasteur from his experiments with fermentation to proof of the germ theory of infection: that invisible germs were the cause of infection and disease.

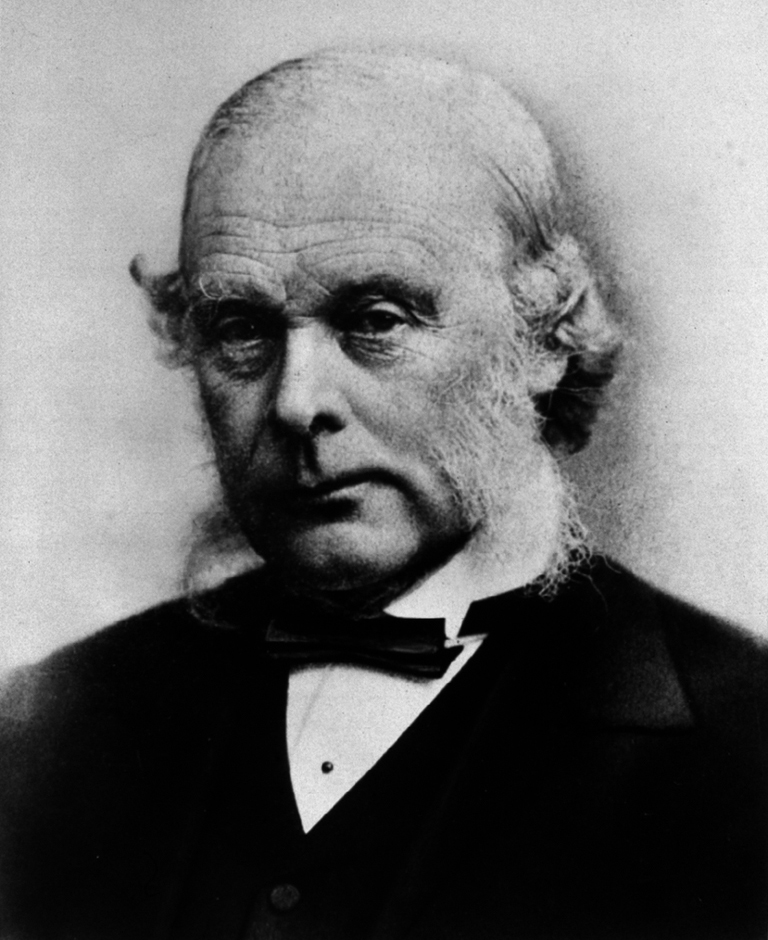

Pasteur’s work revolutionized science and medicine. His discoveries influenced an English surgeon, Sir Joseph Lister, who applied them for the first time to surgery and founded modern antiseptic surgery.

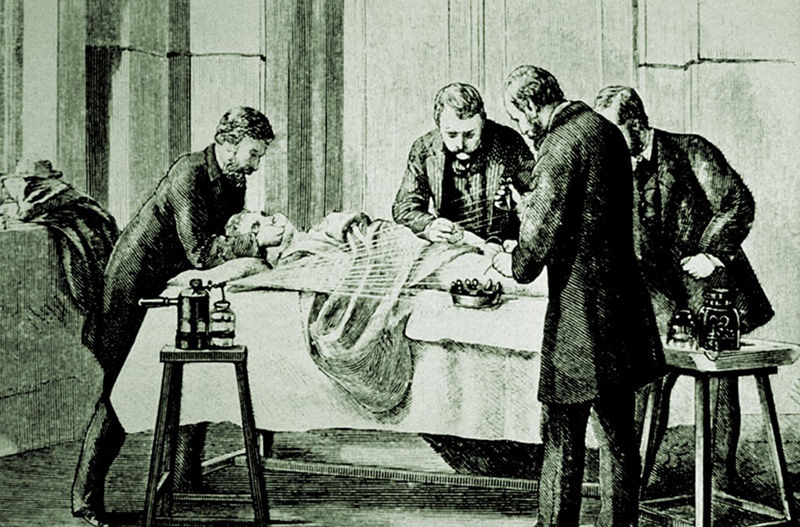

To get an idea of how revolutionary Lister’s idea was, let’s take a look at what operating rooms were like before the advent of modern surgery.

Surgery in the 1800s wasn’t sterile. Surgeons operated in their street clothes – back then, a typical surgeon’s operating room attire was a black frock coat that was rarely, if ever, washed. Surgeons didn’t wash their hands or their surgical equipment. Since most of them thought that surgical infections were generated by a miasma in the air and not by lack of cleanliness, hand washing in the operating room wasn’t required.

Operating rooms weren’t sterile either, and surgical dressings were scraps from the floors of cotton mills. Many surgeons used ordinary sewing needles and thread to close wounds and incisions, and they stuck the needles in the lapels of their coats to use on the next patient. It goes without saying that surgical infection rates were astronomically high, survival rates were low, and people avoided surgery and hospitals at all costs.

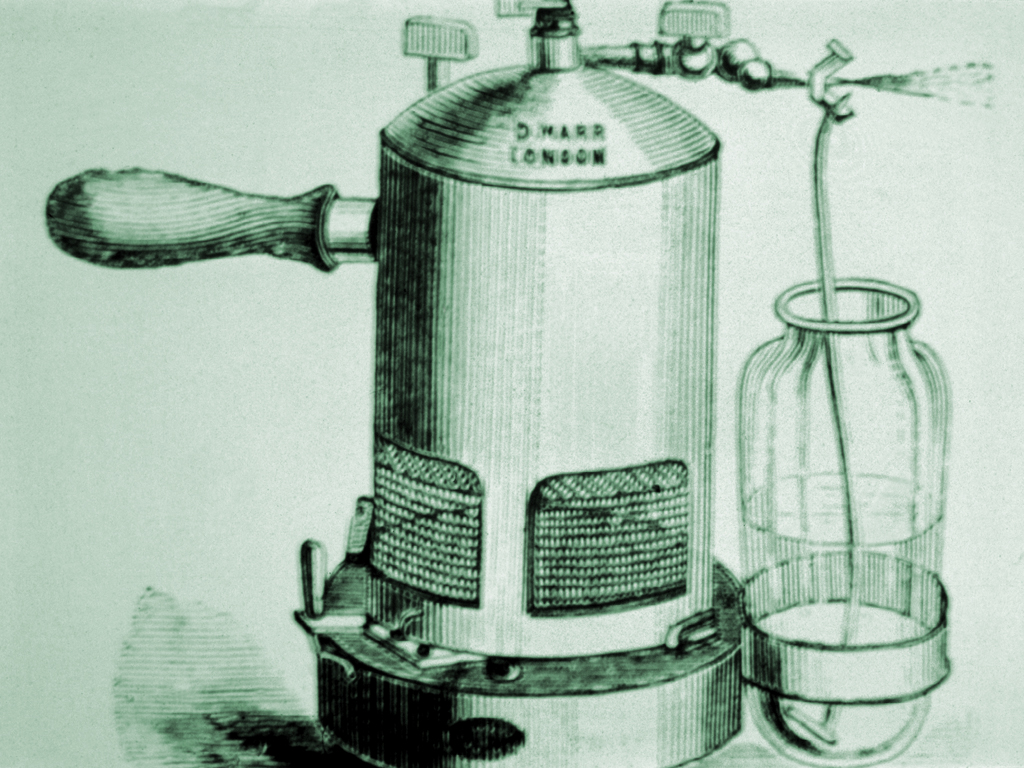

Sir Joseph Lister applied Pasteur’s research to surgery. Lister used carbolic acid as a disinfectant for the surgeon’s hands, the instruments and dressings, and sprayed a mist of carbolic acid throughout the operating room.

Soon, Lister had hard data to back up his belief in antiseptic surgery: his patients started surviving, and they didn’t get the post-surgical infections that were typical of the era. By 1876, when Robert Wood Johnson saw him speak at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, Lister was on the extreme forefront of medical innovation – kind of like a modern TED Conference speaker today. And just as Pasteur’s breakthroughs inspired Lister, Sir Joseph Lister’s breakthroughs inspired Robert Wood Johnson.

So Louis Pasteur’s experiments proved the germ theory of infection, and Sir Joseph Lister applied the results to surgery. But if a surgeon wanted to do sterile surgery, he had to make the sterile dressings himself, just like Lister did, most probably in his kitchen. It was very difficult to do and it was almost impossible to insure and check the sterility of the materials, putting sterile surgery beyond the capacity of all but the largest hospitals.

That’s where Johnson & Johnson came in. Our early mass produced sterile surgical dressings, cotton, gauze and sterile sutures gave surgeons and hospitals the necessary resources to adopt the practice of sterile surgery. With the addition of Modern Methods of Antiseptic Wound Treatment, the best-practices manual on sterile surgery edited by Fred Kilmer and published by Johnson & Johnson in 1888, surgeons could now read the manual, follow the instructions, and use the mass produced products to perform sterile surgery. Sterile surgery was no longer beyond their reach.

Johnson & Johnson also made improvements to the preparation and manufacture of aseptic dressings and sutures, developing new ways to sterilize and package them, giving them a long shelf-life, unlike the less stable home-made methods, and being the first to make cotton absorbent so that it was of better use in surgical dressings.

Word reached Sir Joseph Lister about what Johnson & Johnson was doing, and he wrote a letter to our director of scientific affairs, Fred Kilmer, asking for details. There was a general air of excitement at the Company surrounding the arrival of the letter. Lister’s letter was a great source of pride not only to the Johnson brothers, but to every employee at Johnson & Johnson: he was the inspiration for our founding. By the time of his letter to Johnson & Johnson, Lister had been knighted by Queen Victoria and was known as the father of modern antiseptic surgery. On December 21, 1891, Fred Kilmer sent a lengthy reply to Lister. Here are some excerpts:

“To Sir Joseph Lister, London. Honored Sir – In response to your request for specific information as to the special methods employed in our laboratories in the preparation of surgical dressings and materials used in wound treatment, we cheerfully give herewith our processes in detail, feeling this is due to you, both in answer to a proper request and in recognition of the fact that the whole system of modern wound treatment and the manufacture of materials for the same have been made possible, largely by your labors.” [Excerpt from Johnson & Johnson reply to Sir Joseph Lister, December 28, 1891]

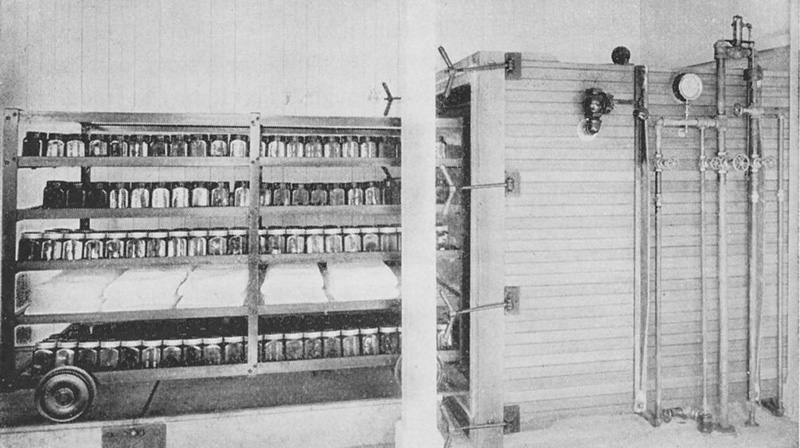

Kilmer followed by describing the Company’s laboratories, and explaining how cotton and other raw materials were cleaned, sterilized and made absorbent. Kilmer mentioned the Company’s water purification and filtration plant (“delivering up to 100,000 gallons per day” he noted), the construction of our Aseptic Room, the training of its employees and the fact that they wore sterile uniforms. He told Lister “Their dress is similar to that of surgeons and nurses in hospital practice.” Kilmer’s letter took Lister through the Company’s aseptic manufacturing practices, including a description of the steam sterilization technique pioneered at Johnson & Johnson.

The letter was signed “Yours very respectfully, Johnson & Johnson.” The inquiry from Lister meant so much to the Company that we later printed our reply in a pamphlet for distribution.

For the Johnson brothers, Fred Kilmer, and our employees in 1891, recognition of their efforts from the founder of antiseptic surgery himself was one of the high points of the year, and filled them not only with pride, but with inspiration to continue forward.

Next post: science and engineering team up to make things happen at Johnson & Johnson in the 1880s and 1890s. Stay tuned.

EXCELLENT ARTICLE!! I feel like I am walking through our company's history from the very beginning in chronological order. I'm waiting for the next one!! thanks, Marcia

Great article with one major error.... Joseph Lister was not English. He was Scottish and hailed from a small town called Bathgate (near Edinburgh)

In reply to by Scott

Hi Scott,

I'm glad you liked the post! Actually, Lister was born in Upton, England in 1827. He moved to Edinburgh in 1853 and in 1860, earned the position of chair of clinical surgery at the University of Glasgow. He came back to England in 1877. This entry in the U.K.'s SurgeonsNet history of surgeons lists his nationality as English: http://www.surgeons.org.uk/history-of-surgeons/lord-joseph-lister.html

He did spend a major part of his career in Scotland, though.

Margaret

I am very glad to read the article, very informative of medical history to the layman of medicine. This article will help in renovating the Museum of History of Medicine of National Institute of Indian Medical Heritage, Hyderabad, India.

Regards,

P.Murali Manohar,

Museum Curator