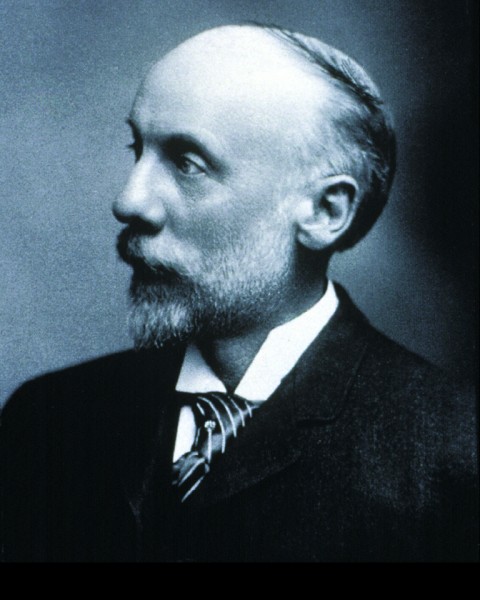

Fred Kilmer: Public Health Volunteer

With this week being National Public Health Week and April being National Volunteer Month, it’s a perfect opportunity to go back in time and let an early Johnson & Johnson employee who was on the front lines of public health improvement talk about some of his volunteer efforts in that area. How can we do that? We don’t have a time machine (despite a Six Degrees of Separation connection to H. G. Wells!), but we do have a first-hand account from one of our employees who spent many years volunteering to improve public health, starting at a time when the field was in its infancy. That employee was our director of scientific affairs Fred Kilmer.

Fred Kilmer moved to New Brunswick in 1879 to pursue his career as a pharmacist. When he arrived in New Brunswick, it was bustling with activity and commerce, but it was like many towns of that era with unpaved roads and decidedly un-modern sanitation. Here’s how Kilmer described it:

“Only a small section of the town was sewered. For the most part drainage ran into the street gutters, which emptied into creeks that passed through the town. Every house had a privy vault. Many had cesspools in their back yards. There were pig pens, cow and horse stables in the midst of the residential areas.” [“Sanitation,” by Fred Kilmer, undated three-page description of his work in public health for the City of New Brunswick, from our archives.]

Those were more or less typical conditions for a town of that size in 1879. But as a new citizen of New Brunswick, a business owner, and a scientist and believer in sanitation and public health, Kilmer was determined to change things.

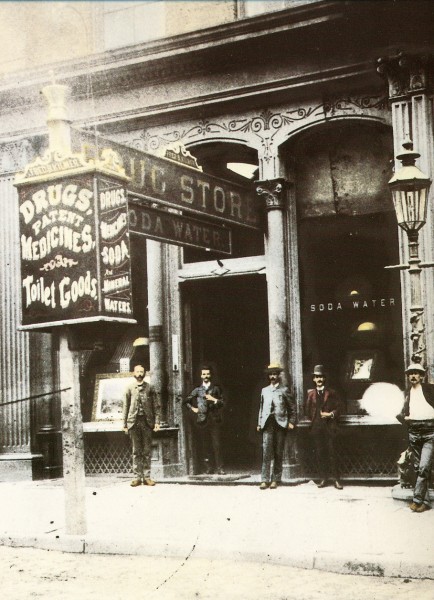

“In the early 80’s [note to blog readers: Kilmer is referring to the 1880s], without knowing what we were driving at, with the mayor and a few physicians we organized a board of health and started in.” [“Sanitation,” by Fred Kilmer, undated three-page description of his work in public health for the City of New Brunswick, from our archives.] At that time, Kilmer was the owner of the Opera House pharmacy. When he joined Johnson & Johnson in 1889, he brought his enthusiasm for improving public health and his knowledge with him to Johnson & Johnson. Soon, Johnson & Johnson was making a variety of public health products and publishing public health material – a natural extension from helping improve surgery to helping to improve public health.

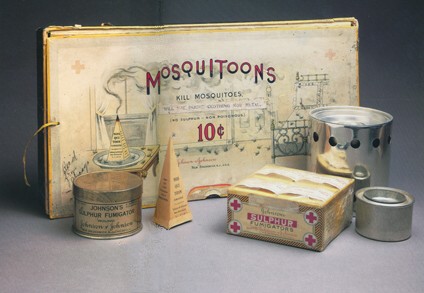

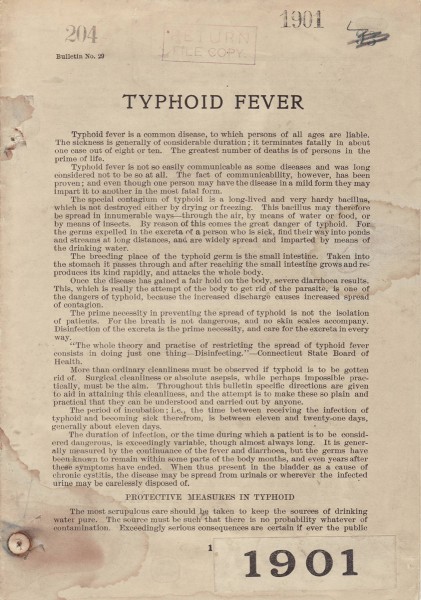

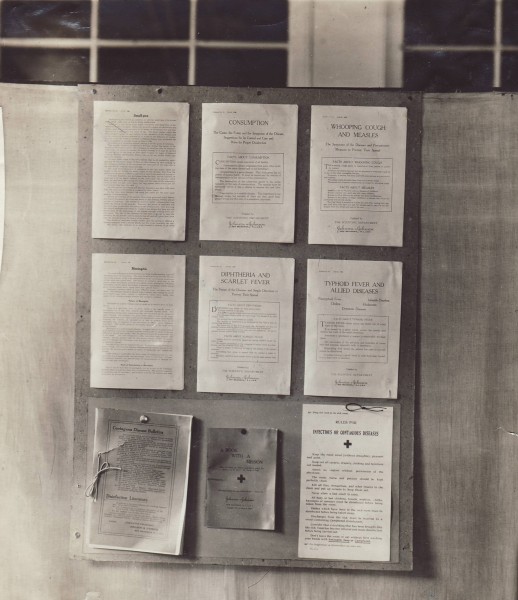

Among the early Johnson & Johnson public health products were vaccination shields, fumigators, disinfectants and antibacterial soaps. The Company also published contagious disease bulletins and other free information to help people protect themselves and their families from contagious diseases.

New Brunswick in the 1880s was a microcosm of typical public health conditions in U.S. cities. In the days before antibiotics and most vaccines, preventing contagious diseases was a key component of public health. Kilmer and the other public health volunteers poured carbolic acid (Sir Joseph Lister’s antiseptic of choice) and chloride of lime into the city’s gutters and sewers to disinfect them and help prevent the spread of disease. In the 1880s, patients with contagious diseases such as typhoid, diphtheria and smallpox were quarantined to protect members of their families and the public. Kilmer remembered one local resident who expressed a certain, er…sharp reluctance when it came to that early public health measure.

“In one smallpox case we were obliged to obtain a warrant from the court in order to attempt to remove the patient. On going to the house we were met by a man inside the door with a raised ax. I still retain this ax as a souvenir.” [“Sanitation,” by Fred Kilmer, undated three-page description of his work in public health for the City of New Brunswick, from our archives.]

Clearly, a dedication to improving public health in the 1800s could sometimes require nerves of steel.

“We succeeded in inducing factories to vaccinate their employees, and sent physicians from house to house to vaccinate the inmates. We were about the earliest in the field in milk inspection work…we went from dairy to dairy, farm to farm, and out of this came the system of report and control.” [“Sanitation,” by Fred Kilmer, undated three-page description of his work in public health for the City of New Brunswick, from our archives.]

Kilmer also worked to get a water filtration system in New Brunswick to make the water cleaner and safer for its residents.

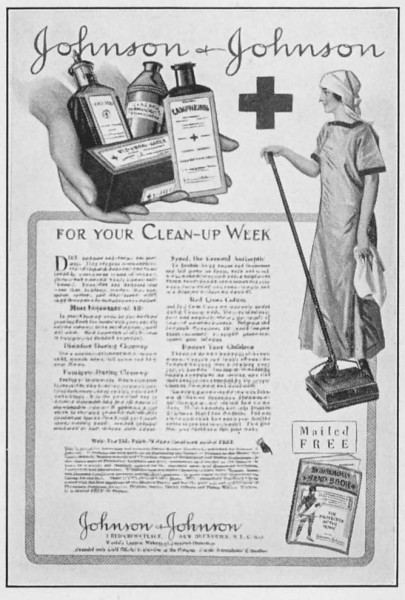

“We instituted a ‘clean-up week,’ which was very helpful in the clearing up of yards, sheds, cellars and atticks. We early began the issuing of pamphlets covering health likes, such as health ordinances; suggestions and regulations for physicians; a description of the milk supply, with a list of dairies and dealers; suggestions to the users of milk; pamphlets on the care and saving of babies, in connection with a baby campaign.” [“Sanitation,” by Fred Kilmer, undated three-page description of his work in public health for the City of New Brunswick, from our archives.]

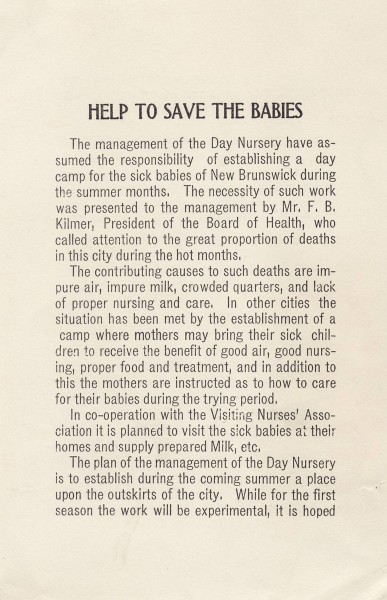

One of those efforts was a day nursery for New Brunswick’s children during the summer months. The day nursery was organized by women volunteers from the New Brunswick community and staffed by the Visiting Nurse Association, with support from the city’s Board of Health.

Along with the clean up weeks, Fred Kilmer and his fellow volunteers on the New Brunswick Board of Health held a series of health exhibits for the citizens of New Brunswick. The exhibits covered the safe handling of milk, hygiene and sanitation, methods to prevent the spread contagious diseases, combating insects, the proper disposal of garbage and more. The exhibits were held in storefronts downtown and attracted crowds of citizens, including teachers and classes from the city’s schools.

In the Nineteen Teens, Johnson & Johnson worked with retail pharmacists to take Kilmer’s “Clean Up Week” idea national, with campaigns every spring and public health information such as A Book With a Mission and The Household Hand Book. These books, made available for free, gave people reliable science-based information on how to recognize contagious disease symptoms, when to call the doctor, and how to use the public health products from Johnson & Johnson to scrub their homes and keep infectious disease germs at bay to protect their families.

“Our work was largely educational, but out of these crude and faulty methods came the great advance in hygiene and sanitation, including the improvement of the water supply, increased sewage disposal, tuberculosis campaign, care of babies, visiting nurse, and a whole host of measures calculated to improving the health of our citizens.” [“Sanitation,” by Fred Kilmer, undated three-page description of his work in public health for the City of New Brunswick, from our archives.]

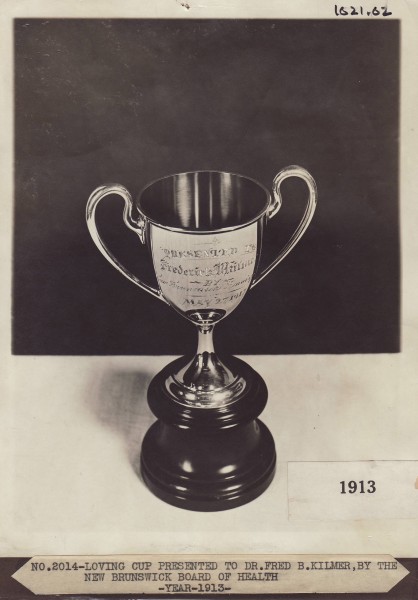

Fred Kilmer retired from the New Brunswick Board of Health in 1913, having served since the 1880s. During his remarks to the Board upon his retirement, Kilmer - always ahead of his time -- advocated appointing women to serve as part of the organization. He continued to advocate for public health improvements both as a citizen of New Brunswick and as an employee of Johnson & Johnson, and he was an important early witness to – and participant in -- the growth of public health in the United States.